Make Feedback Your Superpower

Years ago, at the beginning of my coaching career, I was working with a leader (let’s call her Allie) who was having a challenge with a direct report of hers (let’s call him George).

As Allie described it, George wasn’t showing up to work on time and wasn’t letting anyone – including her – know where he was. People would look for him in the office and, unable to find him, would come to Allie looking for him. And because he hadn’t blocked his calendar or let her know, she was caught off guard. It was a bad look, she was embarrassed at what this implied to others about her leadership, and she was frustrated with George. (This was well before the pandemic and everyone in this organization was going to the office every day.)

To make things worse, George had had a tardy issue previously, and Allie had already addressed it with him. He’d improved for a period, but here they were again. Allie was ready to treat this as a performance problem and write George up. She was done.

But she brought the issue into our coaching work together.

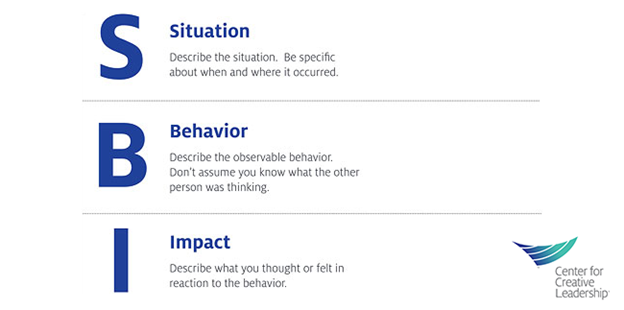

I asked her if she knew why George was showing up late again. She didn’t. So, we worked together on framing up the feedback to George using the Center for Creative Leadership’s Situation-Behavior-Impact (SBI) model.

SBI is my favorite feedback model because it makes the entire process of giving and receiving feedback easier for everyone involved. It does this by making feedback more objective, and it does that by removing assumption of motive from the message.

The feedback giver describes the situation in factual, specific terms, then describes the observable behavior (you can’t observe intent, so you leave it out!), and lastly, the impact that behavior had. Ideally, this is the beginning of a dialogue that invites the receiver to share what they were thinking that led them to behave in a particular way. You can follow up SBI with either a question about intent, a request for a different behavior, or both.

When Allie approached George with her feedback in SBI form, it opened a conversation just as intended. George shared that he and his wife were having challenges in their relationship, and that his primary source of support during this difficult time was his dad. He was staying home in the mornings until after his wife left for work to call his father.

With the intent behind the behavior clear, Allie was able to respond appropriately. She extended empathy and compassion to George, and they were able to work together to find a way forward that would meet his needs, her needs, and the organization’s needs. George began to block his calendar for the first hour of the day should he need that time and to communicate more openly with Allie about his whereabouts. She, in turn, was able to offer support and help him manage expectations from the organization at large.

When done right, feedback can grow a relationship, not take away from it. Allie and George’s story is a terrific example of what this looks like.

What do you think?

Jessica

Founder & CEO

The Sparks Group