When to Stop Digging: Embracing Change and Letting Go

Hello and happy summer!

I hope the summer is treating you well. This summer is busy for The Sparks Group with a trip to Thailand for me (more on that next month!), Anna moving back to the US, and Emily leaving The Sparks Group after six years with us.

It has me reflecting on how hard transition periods are and how many decisions we have to make. Making a decision and sticking with it can feel like the easiest route – except when it’s not. I went to re-read Dr. Linda Hoopes’ (a dear friend and the person who does many of our client engagements on resilience at The Sparks Group) article about the dangers of sticking with decisions even when the evidence suggests we’re wrong. I’m sharing Linda’s article below in the hope that you will find it as helpful as I do. If you love it, consider subscribing to her blog to get regular updates.

Drop me a note and let me know your summer plans. I look forward to hearing from you!

-Jessica

Changing Direction

Digging a Hole

The first rule of holes: When you’re in one, stop digging!

Think about times when you, or someone you know, has boldly stepped up to discontinue a project, end a relationship, sell a house, cancel a trip, or decide you were wrong about an issue despite the forces that were pushing you to keep going. What a great feeling! It’s quite liberating for any of us to get beyond a decision that is no longer serving our best interests.

On the other hand, have you ever watched someone dig themselves deeper into a hole, doggedly clinging to an idea when it’s clear that it’s wrong or pursuing a course of action even when things continue to get worse? Have you found yourself investing increasingly larger amounts of time, energy, and resources in the vain hope of turning around a lost cause?

Escalation of Commitment

Although we may aspire to the wisdom to always make good choices, the “digging a hole” pattern is so common that it has a name: escalation of commitment. Not surprisingly, this pattern shows up in the world of organizational change as well. More often than I’d like to think about, I’ve seen leaders invest additional resources in change initiatives that are failing to deliver results and are not likely to ever achieve their intended outcomes.

Why Do We Do This?

There are a few things that contribute to escalation of commitment. The first, of course, is hope. At its best, hope is a great motivator for leading us to try new things, take chances, place bets on long shots and unlikely outcomes, and seek to beat the odds. This is a wonderful thing, and one of the main positive forces for change. But when hope is not accompanied by logic, it can turn into wishful thinking and a loss of contact with reality.

Humans don’t always think logically. We use heuristics—mental shortcuts—to help us process information; some of these introduce bias into our thinking. One of these heuristics that contributes to escalation of commitment is confirmation bias.

Confirmation Bias

No matter how objective we think we are, we tend to search for, pay attention to, and recall information that confirms our views and ignore, discount, or forget information that contradicts us. And when information can be viewed from multiple perspectives, we tend to interpret it in ways that support our own position. This is especially true when we’re dealing with emotional issues, deep beliefs, and important outcomes. Here are some examples:

- focusing on positive results on a project, seeing them as the result of good planning and judgment, while interpreting problems and negative results as mishaps, flukes, and random events

- reading and listening to information about social and political issues primarily from sources that are likely to agree with us and tuning out other points of view

- ignoring negative information about people we like, while amplifying negative information about people we dislike

Confirmation bias contributes to escalation of commitment by keeping us from seeing the real costs of the situation we are in. We listen to information that tells us we are ok, and dismiss information that tells us we are in trouble, rather than soberly considering all the data and seeing things objectively.

Sunk Costs

A second factor in escalation of commitment is the tendency to put additional resources into an unfruitful course of action. While this sometimes happens through simple inertia (the tendency for things to keep moving in the same direction), it often also involves the sunk cost fallacy—a tendency to place too much importance on the resources we have already invested in a situation (sunk costs) and putting more effort into the current direction rather than cutting our losses and moving on. Here are some examples:

- keeping a low-performing employee because the company has spent a lot of money hiring and training them

- putting additional funding into an organizational initiative in the hopes of recouping the money that has already been spent

- continuing to repair an old car because we’ve already spent so much on it

- staying in an unhappy relationship because we have already invested a number of years in it

- sitting through the second half of a boring movie or finishing an awful meal

Part of the reason for this is that we hate being wrong. When we change our mind after putting time and energy into something, we may feel stupid or silly about our past decisions, or worry that others will judge us negatively for bailing out on a commitment. Sometimes we have made big promises about what we will be able to accomplish. We convince ourselves that if we put in additional effort and resources, we can get things back on track and avoid these negative outcomes, even when the data clearly indicate this is a false hope.

There will always be situations where the investments we make don’t pay off. We may buy a house that declines in value or put significant research and development into a new product that doesn’t do well in the market. We may go on a date with someone who isn’t very interesting once we get to know them. Those are all sunk costs, and they are just part of life. Sunk costs become a problem when they keep us from shifting gears—when we commit additional resources to an unprofitable endeavor rather than investing our resources in a better alternative.

How to Stop Digging

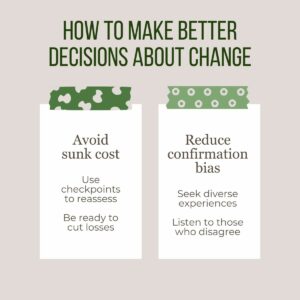

The combination of these two factors can lead to a spiral in which we tune out signs that things aren’t going well (confirmation bias) and invest more resources in a course of action that is no longer serving us (sunk cost fallacy). We can get stuck in a loop that is hard to get out of. Here are some strategies for moving things in a better direction:

1) Reduce Confirmation Bias

The most important step in reducing confirmation bias is being aware of it. This can lead us to look for additional data and take steps to evaluate it objectively. This might include:

- going out of our way to find sources of information that present different points of view1

- listening thoughtfully to people who disagree with us or who raise concerns about our initiatives and strategies

- asking ourselves how we might be wrong rather than trying to prove we are right

2) Reduce Sunk Cost Fallacy

We can do several things to keep sunk costs from biasing our decisions:

- keeping our initial investments low by taking small steps such as experiments and pilots rather than going “all in” on an endeavor at the very beginning

- recognizing and creating “choice points”—opportunities to step back and evaluate progress before deciding to invest additional resources

- making objective decisions based on a fresh look at reality

- getting more comfortable with pulling the plug when our analysis says we are better off cutting our losses2

As we address confirmation bias and the sunk cost fallacy, we can move toward the objectivity needed to make good decisions. However, as we seek to let go of prior commitments in favor of new ones, there are some emotional and logistical factors at play that we need to recognize and attend to:

- “saving face” is important—we need to give ourselves and others opportunities to choose a different path and move forward while maintaining dignity and the respect of others

- focusing on the benefits and gains from the new course of action, rather than just the costs of letting go of the old, will help you sustain your energy through the process of shifting gears

- it’s not always essential to know what comes next—you can step away from one investment of time, energy, and resources without replacing it with something else

- letting go of something that was once desirable is hard—you and others may need time to grieve what has been lost

- you or others may have made personal commitments and promises related to an initiative or endeavor that cannot be fulfilled—recognizing these and having the conversations needed to address them is tough but important

- de-escalation can be gradual—you can choose not to invest further resources in a situation without immediately making a dramatic shift to a different alternative

- stopping a course of action may involve some financial, interpersonal, or other costs—these are normal and are not a reason to second-guess the decision

- others may suffer some losses or negative consequences when a project, relationship, or situation ends—its important to acknowledge and attend to the practical and emotional implications of these situations

It’s immensely satisfying when we feel that we, and those around us, are making good choices about where to invest our time, energy, and resources. This sometimes involves recognizing that we need to change direction. By understanding the forces that can keep us digging when we find ourselves in a hole, we can counteract the tendency toward escalation of commitment, and the contributing factors of confirmation bias and the sunk cost fallacy. It seems to me that this is useful in organizations undertaking change, and also to each of us in the choices we make about our own lives. I hope a few of these ideas take root with you.